There's been so much going on in the news lately -- a lot of it distressing. I've been trying to come up with a way to respond to that in the context of the Daily Apple, and I have obviously failed. I'm not sure how I can give some sort of positive message in response to all these people being shot for various reasons, without sounding all Polyanna-ish, and without saying something you haven't already seen 9,000 times elsewhere. Just know that your Apple Lady is cogitating on all these events and looking for some way to be helpful.

In the meantime, I know one thing I can do that is useful, and that is to find out about Zika mosquito bites. (I am cringing even as I type this, knowing that people are dying from horrific gunshot wounds and here I am talking about mosquito bites. But it's all I've got at the moment, and I have to remind myself that it is more important to contribute something than to do nothing.)

So, my question is, when you've been bitten by a mosquito, can you tell if you've gotten a Zika bite?

The Aedes aegypti is the primary vector -- thing that transmits -- the Zika virus. Only the females sting, so it seems that we're safe from over half the total population of mosquitoes. The trouble is, the Aedes aegypti are extremely common in all sorts of places around the world.

(Photo from Wikimedia Commons via The Verge)

This is what the rash from Zika looks like.

(Photo from Wikipedia)

In the meantime, I know one thing I can do that is useful, and that is to find out about Zika mosquito bites. (I am cringing even as I type this, knowing that people are dying from horrific gunshot wounds and here I am talking about mosquito bites. But it's all I've got at the moment, and I have to remind myself that it is more important to contribute something than to do nothing.)

So, my question is, when you've been bitten by a mosquito, can you tell if you've gotten a Zika bite?

The Aedes aegypti is the primary vector -- thing that transmits -- the Zika virus. Only the females sting, so it seems that we're safe from over half the total population of mosquitoes. The trouble is, the Aedes aegypti are extremely common in all sorts of places around the world.

(Photo from Wikimedia Commons via The Verge)

- No. Bites from a mosquito infected with the Zika virus look and act the same as bites from any other mosquito.

- You might suspect you've got the Zika if you've got a mosquito bite and you also have

- a low fever, less than 102 degrees

- itchy pink rash

- bloodshot eyes resembling pink eye

- sensitivity to light

- headaches

- joint pains

This is what the rash from Zika looks like.

(Photo from Wikipedia)

- But those symptoms can seem like something else, or there may be only a few present, or you may have been bitten by a Zika mosquito and you could have no symptoms of the virus at all. In fact, 4 of 5 people who've been bitten by a Zika mosquito do not show any symptoms.

- The only way to know for sure if you've gotten a Zika bite is to have a blood or urine sample tested within two weeks. But if you have no symptoms, you have no reason to think you'd need a test done, so you may never know if you've gotten a Zika bite.

WHY SHOULD I CARE?

- You may be thinking, if all the thing does to me is make me feel like I have the flu for a week or so, or maybe I feel nothing at all, then what's the big deal? Who cares whether I get the Zika or not?

- Because fetuses as young as 19 weeks old whose mothers become infected with the Zika can suffer a very rare type of brain damage that is so severe, their brains stop growing and so do their skulls. Not only are they born with very small heads, but often the nerves that connect with the eyes and ears do not work properly, they may experience frequent or constant seizures, and they may be unable to move their arms and legs properly.

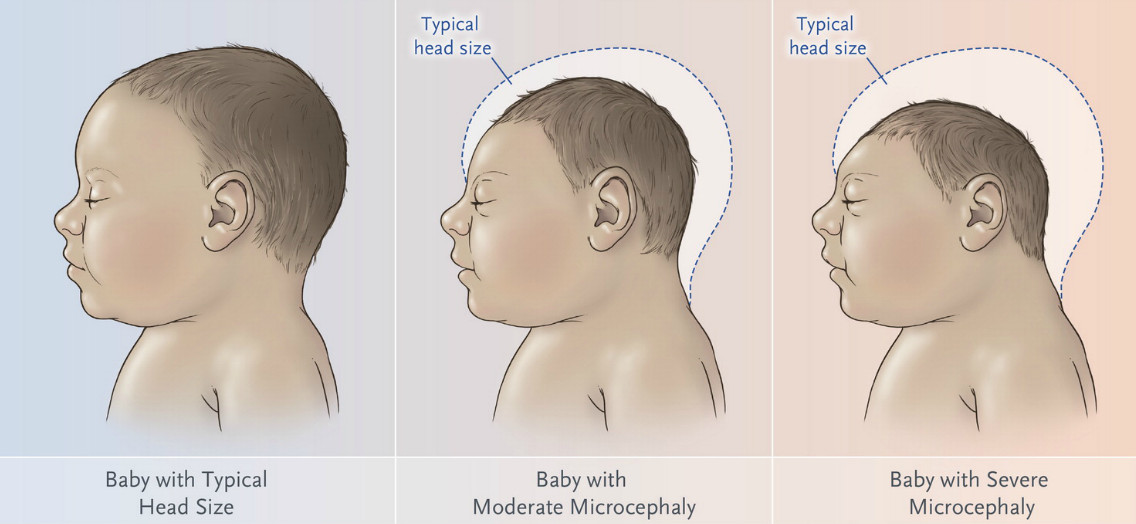

- This condition is called microcephaly (very small head). There is no cure.

- If a pregnant woman gets the Zika, how likely is it that her unborn child will get the microcephaly? Experts aren't sure. Right now, their guesses are anywhere from 1 to 5 percent of pregnancies with Zika resulting in microcephaly.

This is Sophia. She is 2 weeks old and she has microcephaly. She's having a nap before her physical therapy session at a hospital in Brazil.

(Photo by Felipe Dana from the AP, sourced from Stat)

- Sometimes the babies of Zika-infected mothers are born with other types of brain defects including Guillain-Barre syndrome. In this lovely scenario, a baby's immune system will attack its nerves that control muscle movement, pain, temperature, and touch. Results can range from persistent tingling to loss of movement to paralysis and difficulty breathing. It is possible to recover from this syndrome, but it is not fun and for babies it can be very dangerous.

- If you're a man, you should care because it's possible you could transmit the virus sexually. More often, the virus is transmitted by mosquito bites, but somewhere around 10% of cases have been transmitted through sexual contact. Vaginal and anal sex are more likely sources of transmission than oral, but transmission by oral sex is still possible.

- There is no vaccine for the virus, no way to stop its activity once its infected someone. If you've got the Zika, the only thing to do is let it run its course.

- The good news is that if a woman has had the Zika and recovered, and the virus has left her bloodstream, and then she gets pregnant, the baby will not be affected. She will have developed an immunity to the virus.

PREVENTION IS KEY

- Even though it is beneficial to be immune to the Zika virus, researchers and medical professionals certainly do not want people going around trying to infect themselves so they become immune. There have been too few cases for researchers to be certain you might not be exposing yourself to some as-yet-unknown risk. Making yourself sick on purpose is just asking for trouble.

- The best way to protect yourself against the Zika is to

- try to avoid getting it in the first place

- try to avoid passing it on if you've got it

- Avoiding getting the Zika means

- Controlling mosquito populations outside your house.

- Don't give them a place to breed. Since mosquitoes lay eggs in or near shallow water, make sure you don't have places where standing water can develop and be accessible to mosquitoes. This means

- Get rid of or cover things like birdbaths, flowerpots, old buckets or trash cans, etc.

- Tightly cover water barrels

- If a container cannot have a lid, cover it with wire mesh with holes smaller than a mosquito.

This is just the sort of environment mosquitoes love. Standing water, a perfect place to lay their eggs.

(Photo by Sam Hames on Flickr)

- They also tend to hang out in dark, humid places. Spray outdoor insect spray in likely areas, such as under patio furniture, under a deck, behind the garage, etc.

- Controlling mosquito activity inside your home

- Install or repair screens on windows

- Use air conditioning if possible

- Drape a mosquito net over your bed

- Protecting your person from mosquito bites

- Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants

- Use an EPA-registered insect repellent that contains any one of these ingredients

- DEET

- picardin

- IR3535

- oil of lemon eucalyptus*

- para-methane-diol*

- The above ingredients are listed in order of effectiveness (DEET is the most effective).

- * = don't use on children younger than 3 years old

- Don't use insect repellent at all on babies younger than 2 months old. For them, make sure their clothing covers all exposed skin and keep their cribs and strollers covered with mosquito netting.

- Avoiding transmitting the Zika means

- For 3 weeks after having been in an area where the Zika virus has been identified,

- Practicing safe sex by using condoms.

- Or don't have sex at all.

- Following the steps listed above to control mosquitoes and to try to keep from being bitten and thus infecting a mosquito who could pass the virus on to someone else.

- Where have Zika cases been identified?

- This information changes frequently. As of this writing, areas range from Mexico and Central and South America, to Egypt and several countries in Africa, India, Pakistan, and Indonesia, and several countries in Southeast Asia.

- It has recently also been identified in most states in the US. Utah is the first state to have seen a fatality from Zika.

- For current information, check these pages from the CDC:

WHAT IS ZIKA ANYWAY?

- The Zika virus has been known to exist since the 1940s when it was first isolated from a rhesus monkey in the Zika Forest in Uganda -- hence the name.

- (Originally it was spelled Ziika. The word means "overgrown.")

- The virus was first identified in a human in the 1950s.

- It is in the same family of viruses as dengue fever and West Nile and some 60 or so other viruses.

- Incidence was restricted mainly to Africa and tropical parts of Asia. But in recent years, the virus has spread rapidly.

- Reasons for the virus's rapid transmission may include

- increased global travel

- urbanization (more people moving into mosquito-rich areas)

- climate change (more areas becoming warmer and friendlier to mosquitoes)

- It seems that the number of microcephaly cases have risen because the number of Zika cases have risen to a correspondingly increased extent.

(Image from the New England Journal of Medicine, sourced from Vox)

As the Wesley twins said, much to their own surprise, "Safety first."

Or as one infectious disease specialist who's been studying the virus said, "It's not a verbal exercise. It's people's lives. Babies' lives and welfare are at stake."

Sources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Zika Virus -- a multitude of resources here

The New York Times, Short Answers to Hard Questions About Zika Virus, June 24, 2016

Alana Romain, Romper, Does a Zika Mosquito Bite Look Different than Normal Mosquito Bites? [No] March 16, 2016

PBS Newshour, How many Zika-infected infants will develop microcephaly and other FAQs, May 20, 2016

World Health Organization (WHO), The history of Zika virus

The Verge, Climate change and urbanization are spurring outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases like Zika, February 10, 2016