To the point: the other day, I watched a political video on YouTube. Then I read the comments people had posted below it. Several people accused other commenters of employing straw man and ad hominem arguments and said that their statements were therefore unsound (in fact, they yelled these things at each other). I saw those phrases "straw man" and "ad hominem" enough times that I finally had to go look them up.

Once I did, I realized I kind of already knew that arguments like that were suspect, I just didn't know the name for them or why they didn't work. And then I thought, OK, so now I know what these are, how do I recognize them in those political ads? And once I know that, then what do I do?

Well. Let me break down these questions for you one at a time. First, the definitions of some of those terms.

FALLACIOUS ARGUMENTS

People make fallacious arguments in all sorts of contexts. They show up in lots of places, not just politics, but politics is where they seem to rear their head the most often or the most visibly. One of the reasons people use fallacious arguments a lot is because it's easy to do, and even though the arguments are logically unsound, they are often very effective anyway.

Here are a couple common ones that also require a little extra explication.

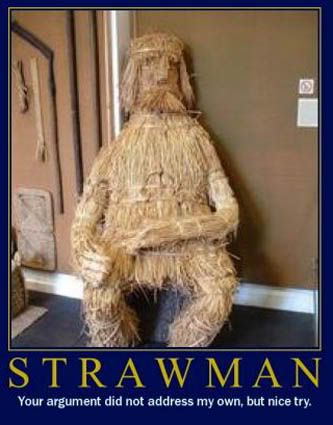

(Image from hardluck_01 on Photobucket)

Straw man: Instead of engaging with a particular topic that you have proposed, your opponent swaps it for something else and takes issue with that.

- The topic that has been swapped is one that is much easier to take issue with, a "straw man" rather than a "real man."

- The sign that someone has pulled a straw man: you find yourself arguing about a completely different subject than the one you started out with. If the second subject seems to burn with controversy, that's another good sign.

- Famous examples: "If you support [fill in the blank], you're just like Hitler."

- Sample conversations in which a straw man appears:

- Person 1: What do you think of the proposal to cut the budget for the swimming pool?

- Person 2: It's further evidence of how much this school hates athletes.

- analysis: Person 2 has turned the subject from focusing on the budget to a perceived animosity toward a group of people. Person 1 will likely feel the need to try to prove that the school does not hate athletes before the topic of the budget can be addressed.

- It's very tempting to make a straw man argument. Assigning meaning to things is one of the most important tools we use to help ourselves make decisions. It's hard to engage with a topic as apparently boring or unfathomable as a budget. But if we can say what it means that the budget is getting bigger or smaller or whatever it's doing, then we know how we're supposed to respond. Similarly, most of us have no idea why we should vote for this guy or the next guy, but if I can say that guy #2 is like Hitler, then we'll sure as heck know what to do!

- What to do when faced with a straw man: ask your interlocutor to get back to the topic at hand. Try posing the question in a different, perhaps less open-ended way: "Do you think the swimming pool budget cut is too big?" You'll get a yes/no reply in answer to that one.

- Alternatively, present your interlocutor with additional facts: "Are you aware that the budget for the swimming pool is currently five times that of the budget for the music program?"

- Or ask your interlocutor to provide you with facts: "Do you know how the swimming pool budget compares to any other item in the budget?"

Ad Hominem: literally, "concerning the man." Instead of attacking a person's argument, you attack the person's character.

- It's not the same as outright name-calling, but when you're saying bad things about somebody (or good things) and using that to justify a decision, you're pulling an ad hominem.

- The sign that an ad hominem has occurred: name-calling.

- Typical examples:

- "Vote for Candidate X for Congress because he and his family are really good-looking." (as if the appearance of one's family would make one a good politician.)

- "Don't vote for Candidate X for Congresss because she's too brainy." (as if intelligence would make one a poor politician.)

- "Don't vote for Candidate X for Congress because he's rich and doesn't understand us regular people." (as if wealth would make one a poor politician.)

Here's an interesting example. The speaker is clearly engaging in ad hominem: don't support the other guy because he's a wolf. But the cartoon itself is engaging in ad hominem, depicting the speaker as a wolf, albeit in sheep's clothing. The difference is, the cartoon is basing its depiction on a specific thing the speaker is doing. Even so, more evidence is probably warranted.

(Cartoon from Caracas Chronicles)

- The ad hominem gets iffy when the name-calling seems to be relevant. For example, if you say, "Don't vote for Candidate X because she cheated on her tax return," the suggestion is that because she cheated on her tax return and was not trustworthy in that one instance, she would therefore not be trustworthy in all instances, and would therefore make a poor politician.

- You can't make all of those conclusions based on that one instance in the past. But we do make those kinds of judgments all the time. Perhaps the most famous example of an ad hominem is what happened to President Clinton. It was more complex than this, but essentially, President Clinton got impeached because he did receive oral sex from Monica Lewinsky and he lied about it. People assumed that, since he cheated on his wife and lied about it, who knew what else he was lying about; he must therefore be an untrustworthy President, and he got impeached (by the House only, but still).

- Sometimes a person's character is admissible in making decisions. Think about the drug addict who takes the stand as an eyewitness. His or her testimony is going to be colored by the possibility that he or she may have been under the influence at the time. So sometimes an ad hominem is a valid argument.

- What to do when faced with an ad hominem: ask your interlocutor to spell out how it's relevant. "How does Candidate X's physical appearance/personal wealth/intelligence help/hurt when it comes to being a politician?" At the very least, you might uncover some interesting relationships your interlocutor has made between one facet of a person's life and another.

Slippery Slope: begins at one position and says that this will inevitably lead to the next worst thing, then the next worst thing, until it finally ends at something just shy of apocalypse, and so therefore the position where we started must not be allowed.

- Doesn't allow for the possibility that the chain of events could be stopped at any point before reaching the apocalypse.

- Signs of a slippery slope: a list of possible events, each one more terrible than the last. There's usually also some exaggeration in one or more of the events.

- Famous slippery slopes:

- Marijuana is a gateway drug: anyone who does marijuana will try the next harder drug and so on until they wind up hooked on heroin.

- The rationale for the Vietnam War, a.k.a. the Domino Effect: if we allow Vietnam to "go communist," communism will inevitably spread to each country in Southeast Asia until all of Asia is communist.

- Even though this technique is logically false, it can be effective anyway because it plays on people's fears. Usually the last thing we hear is what rings in our ears and we tend to react to that. "What's that you say? Eating Blow-Pops will lead to epidemic diabetes, which will mean the death of thousands of children?! No, of course I don't want thousands of children to die! Down with Blow-Pops!"

These are not agents of widespread death and destruction. They're just Blow-Pops. Now that I think of it, though, since they start out as hard candy and then become gum, maybe Blow-Pops are themselves a slippery slope... candy for suckers.

(Photo from Mast General Store)

- The tricky thing about slippery slope arguments is that tucked among the reactionary fear, there may actually be a plausible mechanism by which accepting one event may lead people to accept the second and then the third. However, to make a slippery slope argument even somewhat valid, you have to bolster it with specifics about exactly how people could make that transition.

- Trudy Govier, writing about the "Famous, or Infamous, Slippery Slope," explains it better than I can. Taking the example of legalizing assisted suicide in turn leading people to accepting the murder of disabled people and the devaluing of all life in general, she says:

The burden of proof is on people who appeal to slippery slope arguments to argue against assisted suicide. They need to buttress their arguments by explaining just how and why people would be led from supporting assisted suicide to supporting the killing of the handicapped and to de-valuing life itself. They then need to recognize that in exploring the likelihood of unintended consequences, they have entered the territory of probabilities and the balancing of pros and cons. At that point, they will enter into a debate with supporters of assisted suicide where they will be engaged in considering reasons, risks and safeguards. . . . Carefully amended and qualified in this way, a slippery slope argument would not be a fallacy. But the amendments allow that it is far from a compelling argument. It only gives one consideration supporting the claim that illegitimate actions might come to be condoned.

- In other words, if you find yourself faced with a slippery slope argument, ask your interlocutor to break down the chain of events and, step by step, provide specifics about how each step will necessarily occur as a consequence of the first one. If they can't provide that breakdown, they don't get to have all the events in their chain reaction.

- Alternatively, here is one of my favorite rebuttals to slippery slope arguments: "Getting out of bed in the morning is a slippery slope."--Michael J. Fox

Next up: I'm going to take two political ads and parse out the logical fallacies in each.

Sources

Don Lindsay, A List of Fallacious Arguments

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Fallacies

WiseGeek, What is a Straw Man Argument?, What is a Red Herring?

Fallacy Files, Straw Man

Quartz Hill School of Theology, Logical Fallacies

Trudy Govier, Humanist Perspectives, The Famous, or Infamous, Slippery Slope

great guide to debating common fallacious arguments.thanxx

ReplyDelete