So I've been away on vacation, and I read about those derechos that hit several states. They didn't hit where I was, and I had zero access to the internet or TV. Those of you at home may have heard all sorts of explanations and definitions of a derecho already, but I had only a smallish daily newspaper, so I did not. Now that I'm back among the swirl of telecommunications, I want to find out about these derechos.

The June 2012 derecho on the southeast side of Chicago.

(Photo from Twitter, sourced from The Original Weather Blog)

Mainly I want to know, what the heck are they, and is this some new term the meteorologists have cooked up? Is this a sign that global warming is getting crazy?

Radar image of the derecho on June 29, 2012 (my birthday, by the way, and this is the second one to happen on my birthday). This derecho was especially widespread, sweeping across 700 miles.

(Image from the National Weather Service, sourced from Wikipedia)

The June 2012 derecho on the southeast side of Chicago.

(Photo from Twitter, sourced from The Original Weather Blog)

Mainly I want to know, what the heck are they, and is this some new term the meteorologists have cooked up? Is this a sign that global warming is getting crazy?

Definition

- NOAA's Storm Prediction Center says that a derecho is a

- widespread

- long-lived

- wind storm,

- accompanied by rapidly moving rain or thunderstorms

- I'll take each of those attributes in turn.

- Widespread: extends in a swath of more than 240 miles or greater along most of its length. In other words, the storm encompasses a huge amount of territory all at once.

Radar image of the derecho on June 29, 2012 (my birthday, by the way, and this is the second one to happen on my birthday). This derecho was especially widespread, sweeping across 700 miles.

(Image from the National Weather Service, sourced from Wikipedia)

- Long-lived: this one seems to be inaccurate, since your experience of a derecho might seem relatively brief, only about ten or fifteen minutes. But the key is that the derecho spans the entire 240+ miles, and the entire storm continues along that span for several tens of minutes. What's more, the system may take as long as 24 hours to develop and its entire lifespan can last 2 days.

- Wind storm: wind gusts have to reach at least 58 mph for the storm to get called a derecho. Why 58, I don't know. Seems pretty random, but that's what NOAA says. Sometimes winds can exceed 100 mph.

- The wind storm attribute has another important aspect, which is that while tornadoes spin and hop about, dropping down to inflict damage in a few places and hopping up to move someplace else, the derecho moves in a straight line across an area. So a derecho is sometimes described as inflicting "straight-line wind damage."

- In fact the word derecho is Spanish for "straight ahead" or "direct." (More on the word origin in a bit.)

This field of corn in Indiana has been all smashed down by the high winds of the 2012 derecho. Gives a pretty good sense of a derecho's straight-line, strong winds.

(Photo from the DuBois County Free Press)

- Accompanied by fast-moving thunderstorms: usually there are several thunderstorms happening within the band, or bow, of the derecho. There can be all sorts of downbursts, sometimes occurring a fair distance apart, or clustered together, or ganged in one big swath. The downbursts themselves can individually last a brief time, but as the entire bow of the derecho moves across the landscape, more downbursts can get whipped up and release their rain.

You've probably seen this image of the 2012 derecho all over the place. This was taken in La Porte, Indiana. The front line is clearly visible here. That's typical of thunderstorms, but this is like a line drawn in the sky with a ruler. And you can just tell by those roiling clouds that they are not messing around, this is going to be a big-ass storm.

(Photo by NASA Goddard Photo and Video)

- The damage caused by a swath of downbursts can be similar to the damage caused by a tornado. What's more, a tornado or tornadoes can occur within a derecho. During a May 2009 derecho, 45 tornadoes were reported.

- The damage a derecho can cause typically includes uprooted and fallen trees or utility poles; overturned boats, SUVs, or even cars; collapsed barns and small buildings; and flying debris including tree limbs, roofing material, broken glass, etc. Power lines are also very vulnerable, and power outages that last for extended periods of time across large areas are very likely.

- In the June 29, 2012 derecho, 3 million homes were without power, 12 people were killed, and 20 people were injured.

This is in the DC area, after the 2012 derecho. The root mesh is sticking up 10 feet in the air, which gives you an idea of how large this tree is. Note the power lines pulled down by the tree. This sort of thing happened all over the place, which is one of the reasons it took so long for the power to get turned back on for so many people.

(Photo by woodleywonderworks on Flickr)

How, When, & Where Derechos Form

- Meteorologists have a tough time predicting derechos for several reasons:

- because derechos encompass so much territory, and it's hard to amass all the data in time to put together that big a picture.

- because sometimes a derecho can form very rapidly when several thunderstorms suddenly gang together to form one great big storm

- because meteorologists still don't understand enough about how and why they form

- But some things about how derechos form meteorologists do feel fairly sure of:

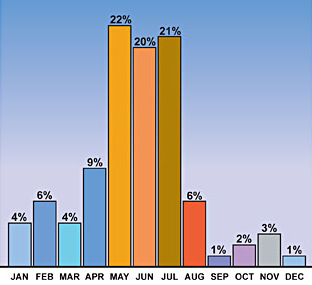

- They happen most often in May, June, and July. These months are when thunderstorms are more likely to occur.

Months when derechos are most likely to happen in the United States

(Graph from NOAA)

- They often happen in the midst of a heat wave. When a large upper-level high pressure system just sits over the Midwest, something called an elevated mixed layer (EML) of air forms. This means that above the place where the hot air is just sitting, as you move higher into the atmosphere, the temperature drops rapidly with each incremental climb. There's no breeze mixing up or even moving the hot air down below, so it gets all concentrated there, and the cool air up above doesn't move around either. Big differences in air temperature is the main thing that results in big storms.

- They may also happen in early spring or early fall. This is less common, but it can happen. Derechos that spring up during these times are a little different, since they're associated with very strong low pressure systems, as opposed to those long-lasting high pressure systems.

- They tend to occur east of the Rockies. The Rocky Mountains are tall enough that that big fat layer of hot air can't sit in one place low to the ground, so the EML doesn't develop above it. This is why derechos usually happen in the Plains states or in the Midwest, or occasionally along the Atlantic.

Map showing how likely derechos are to occur in various parts of the United States. From this map, it looks like derechos never occur west of the Rockies. That isn't exactly true; they have happened in the West, but extremely rarely.

(Map from NOAA)

I wonder if the stratifications visible in this cloud -- which is the 2012 derecho -- are the stratifications that occur in the elevated mixed layer.

(Photo from WordlessTech)

Derechos and Global Warming?

- By now you've probably gathered that derechos have been known to meteorologists for a while. The term was first coined by a physics professor, Dr. Gustavus Hinrichs, at the University of Iowa, in 1888. One of the storms he used as a basis for his term occurred in 1877.

Hinrich's figure depicting a storm he was the first to call a derecho sweeping across Iowa in 1877.

(Image from NOAA)

- So they're nothing new. It's apparently only that the term hasn't entered common (that is, non-meteorological) parlance until recently.

- Since derechos are often linked with heat waves, it is tempting to think that if global temperatures rise, we may see more derechos in the future. But meteorologists hesitate to make such a leap. For one thing, they say they don't have enough data to

- make a definite link between greenhouse gas emissions and heat waves, or indeed any weather pattern associated with derechos

- come up with any consistently reliable weather pattern for derechos in general. They simply don't have enough records or enough data about derechos to make these kinds of sweeping generalizations about them.

- In fact, while they have a list of derechos that have occurred in the past, they say right up front that they know the list isn't complete. All the sites I checked on this refer to NOAA's list of "noteworthy" derechos, which is to say, it's nowhere near all of them.

I don't have anything insightful to say about this photo other than holy crap, look at that thing. This is Minnesota, June 29, 2012.

(Photo by Brittney Misialek for the Minnesota Star Tribune)

- So there's no way to be certain of all sorts of things; for example, how many derechos happened in the late 1800s when the term was first coined, or even before that. Which means scientists can't compare the frequency now with the frequency then and therefore can't draw any real conclusions.

- The list of noteworthy derechos, in chronological order, goes like this:

- July 4, 1969: Ohio Fireworks Derecho

- July 4, 1977: Independence Day Derecho

- July 4-5, 1980: More Trees Down Derecho

- June 7, 1982: Kansas City Derecho of 1982

- July 19, 1983: I-94 Derecho

- May 17, 1986: Texas Boaters' Derecho

- July 28-29, 1986: Supercell Transition Derecho

- May 4-5, 1989: Texas Derecho of 1989

- April 9, 1991: West Virginia Derecho of 1991

- July 7-8 1991: Southern Great Lakes Derecho of 1991

- March 12-13, 1993: Storm of the Century Derecho

- July 12-13, 1995: Right Turn Derecho

- July 14-15, 1995: Ontario-Adirondacks Derecho

- May 30-31, 1998: Southern Great Lakes Derecho of 1998

- June 29, 1998: Corn Belt Derecho of 1998

- Sept 7, 1998: Syracuse Derecho of Labor Day; NYC Derecho of Labor Day

- July 4-5, 1999: Boundary Waters-Canadian Derecho

- May 27-28, 2001: People Chaser Derecho

- July 22, 2003: Mid-South Derecho of 2003

- May 8, 2009: Super-Derecho of May 2009

- June 28, 2012: (not yet named as far as I know)

- Now here's what they look like put on a timeline:

- According to this very incomplete data, it's tempting to conclude that there was a spike in activity in the mid-to late 1990s and that it's declined again. But you can't make that conclusion because this isn't all the derechos that have occurred, only the noteworthy ones. So it's impossible to say whether they're increasing in frequency or not.

- Many meteorologists say that you can expect about one derecho every year or two somewhere in the US. Usually they're not as huge as the one we had this year, though.

Derecho from May 27-28, 2001 near Fort Supply, Oklahoma.

(Photo from NOAA, by Douglas Berry)

- Some evidence suggests that derechos seem to be more damaging because shade trees planted in the postwar years in urban and suburban areas are now matured, so many more trees have fallen in recent years.

- So the final answer on the relationship between derechos and global warming is maybe.

Man, the wind pulled up that tree and the grass like it was sitting in carpet. This is in Vineland, NJ, and that's Grace.

(Photo from MyFoxPhilly, taken by Margaret Hartman)

Sources

NOAA Storm Prediction Center, About Derechos

Kristina Pydynowski, Intense Storms Called a "Derecho" Slam 700 Miles of US, AccuWeather.com, July 2, 2012

ABCNews Good Morning America, "Derecho" Storm Ravaged Washington Area, July 2, 2012

Jason Samenow, Did global warming intensify the derecho in Washington, D.C.? Washington Post Local, July 5, 2012

NOAA Storm Prediction Center, About Derechos

Kristina Pydynowski, Intense Storms Called a "Derecho" Slam 700 Miles of US, AccuWeather.com, July 2, 2012

ABCNews Good Morning America, "Derecho" Storm Ravaged Washington Area, July 2, 2012

Jason Samenow, Did global warming intensify the derecho in Washington, D.C.? Washington Post Local, July 5, 2012

Welcome back; happy birthday; awesome post!

ReplyDeleteThanks so much, uzza!

ReplyDelete