I don't know if this still happens in schools as much anymore, but I remember fall and back-to-school as being the time for school pictures. It seems to me that the practice of schoolchildren getting their portrait taken by some photographer who shows up one day a year, and then the parents purchasing several copies of that picture has become pretty much ensconced in our culture (at least, until digital cameras and Flickr and Facebook made that practice of less value to parents).

So my question is, how did this practice get so established that we pretty much take it as a given that somebody is going to show up at school and take pictures of every single kid in school, and then sell those photos to the parents?

This poor girl looks like she has no idea what has happened to her, why someone has dressed her in that way-too-big cap and gown, and put her in front of that stupid background. Hey, it's a class photo. We all look weird in those things, it's just a question of degree.

(Photo from AMC School Photography Service)

This now-famous photo of Edgar Allen Poe is an example of a Daguerreotype. You can't tell from this version of it, but Daguerreotypes have an almost hologram-like quality. This is because of the highly-polished, reflective nature of the silver on which it is made.

(Photo from Wired)

Photo taken by George K. Warren of the grounds at Harvard University in the early 1860s.

(Photo from Luminous Lint)

George W. McNeel, in his 1859-1860 Rutgers yearbook, photo & album made by George K. Warren

(Image from the Smithsonian)

Photo of George K. Warren, the photographer who took the pictures in George McNeel's Rutgers yearbook, complete with this inscription: "Photographically I am yours, my dear McNeel. Geo. Kendall Warren."

(Image from the Smithsonian)

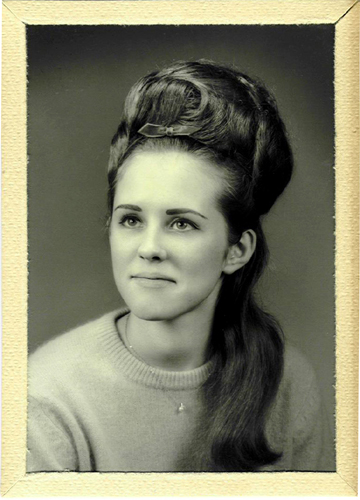

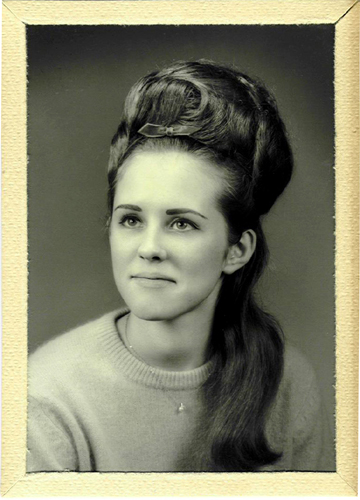

Here's one delightful class photo from the archives. Sadly, I don't know her name. Or the name of her hairdresser.

(Photo from Blogging Bistro)

This yearbook photo is of someone currently famous. Any guesses? Answer at the end of the entry.

(Photo from the angry dome)

Sooner or later, everybody makes the dorky-class-photo face.

(Photo from a page of nothing but photos of some kid named Nick)

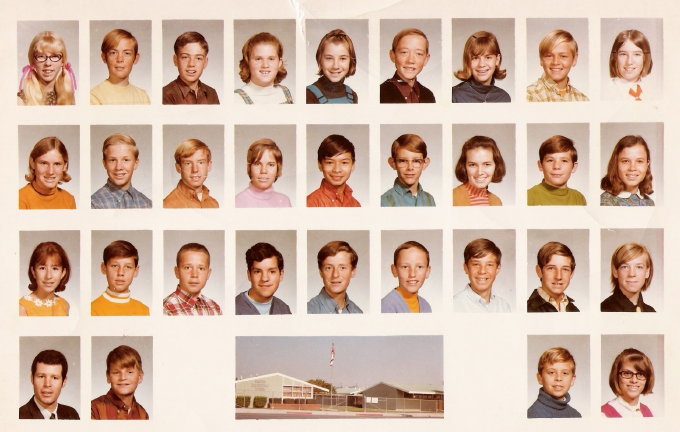

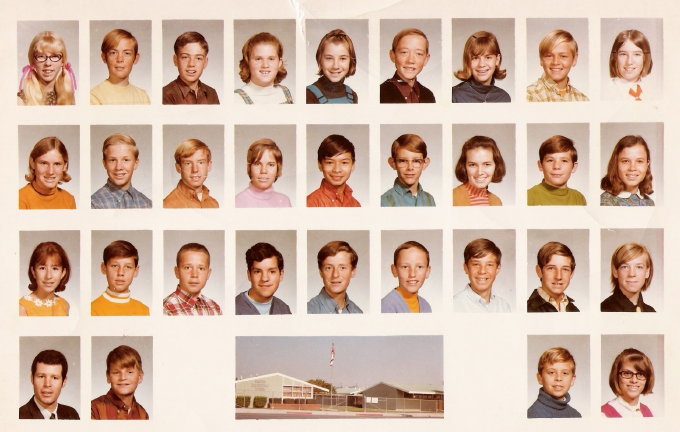

Do they still do these class composite photos? I hope so. This one is from Mr. Fine's 8th grade home room, Newton Elementary School, Torrance, CA, 1969.

(Photo from Gary Chang's Scrapbook)

Then there's the technological advancement of superimposing two images in the same print, which allows for wondrous photographic achievements such as this.

So my question is, how did this practice get so established that we pretty much take it as a given that somebody is going to show up at school and take pictures of every single kid in school, and then sell those photos to the parents?

This poor girl looks like she has no idea what has happened to her, why someone has dressed her in that way-too-big cap and gown, and put her in front of that stupid background. Hey, it's a class photo. We all look weird in those things, it's just a question of degree.

(Photo from AMC School Photography Service)

- It turns out, the practice of taking school pictures starts with pretty much one photographer, George K. Warren in the late 1850s.

- George had a photography studio in Lowell, Massachusetts which he opened in 1851. He was producing his photos using the Daguerreotype method.

This now-famous photo of Edgar Allen Poe is an example of a Daguerreotype. You can't tell from this version of it, but Daguerreotypes have an almost hologram-like quality. This is because of the highly-polished, reflective nature of the silver on which it is made.

(Photo from Wired)

- Daguerrotype photography, by the way, meant you had to take a copper plate which was coated with silver, polish the silver until it was smooth as a mirror, put it in a closed box with some iodine, and then you could use it to take the picture. After you took the picture, then you have to develop it over a pool of hot mercury, and then fix the image using some chemicals, one which included gold.

- So that was an expensive process, it was time-consuming, and it was dangerous (though they probably didn't know that at the time).

- After running his studio the Daguerrotype way for a few years, Warren decided to switch to a new, different process which used glass negatives. He wasn't the only one making that switch, but what he did with the process was different.

- With a Daguerrotype, you had one image and one print. Negatives meant you could make several prints from one image.

- George asked himself, who would want several copies of the same photo? His answer? Schools! (well, specifically, colleges.) This wasn't too much of a leap, since he lived near Boston and you practically couldn't swing a cat without hitting a college.

- But he thought that students graduating from college would like to take pictures of their classmates back home with them. So he created photo albums, one photo per page, of the students graduating that year. (Yes, this is also the story of the first yearbook.)

- He made arrangements with all sorts of colleges and universities -- Harvard, Brown, Williams, Rutgers, Union College, Phillips Academy -- that they would buy a minimum number of his photo albums. Then he set up appointments to take portrait photos of students, their professors, the college presidents, even the housekeepers. He also took photos of the buildings and grounds.

Photo taken by George K. Warren of the grounds at Harvard University in the early 1860s.

(Photo from Luminous Lint)

- (Recognize the business of a photographer from elsewhere making appointments with lots of schools ahead of time? Securing commitments that people will buy so many photos before the photographer even shows up?)

- After taking the photos, Warren went back to his studio in Lowell, produced the photos from his negatives, trimmed them, mounted them on individual pages, and sent them to a bookbinder to be bound. The bindery also embossed the name of the school on the cover, and in some cases, added the name of the student who would be the purchaser of that album.

- How do we know all this? The Smithsonian has one of those photo albums of George K. Warren's. That particular album belonged to George W. McNeel, a Rutgers student whose senior year was 1859-1860.

George W. McNeel, in his 1859-1860 Rutgers yearbook, photo & album made by George K. Warren

(Image from the Smithsonian)

- In true yearbook fashion, people signed it. Except they didn't write messages like, "Have a good summer," or "Party hardy." Their messages were more like letters. And they were written by classmates and instructors both.

- Something else a little different about this yearbook was that George Warren included a photo of himself.

Photo of George K. Warren, the photographer who took the pictures in George McNeel's Rutgers yearbook, complete with this inscription: "Photographically I am yours, my dear McNeel. Geo. Kendall Warren."

(Image from the Smithsonian)

- His idea really caught on. At one college in one year, he made over $1,000. In today's money, that would be $3,700. From one school. And he visited several, each year.

- Today, following in Warren's footsteps, photographers who work for a company or studio (Lifetouch may be the largest; they photograph some 20 million students each year) make arrangements ahead of time with several schools. These companies aren't visiting colleges as much as they are going to grade schools and middle schools, but it's the same idea.

Here's one delightful class photo from the archives. Sadly, I don't know her name. Or the name of her hairdresser.

(Photo from Blogging Bistro)

This yearbook photo is of someone currently famous. Any guesses? Answer at the end of the entry.

(Photo from the angry dome)

Sooner or later, everybody makes the dorky-class-photo face.

(Photo from a page of nothing but photos of some kid named Nick)

- Today's school photographers sit the students down in front of a fake backdrop, tell them to smile, and take their photos. One at a time. That's about the same as the way George Warren did it, too.

- They do now manage to take everybody's picture in a day or two. That's probably a lot more pictures in a lot less time than George Warren did it. But the multiplicity of it is similar.

Do they still do these class composite photos? I hope so. This one is from Mr. Fine's 8th grade home room, Newton Elementary School, Torrance, CA, 1969.

(Photo from Gary Chang's Scrapbook)

- Today, it's not the students buying the photos but rather the parents. And, from what I've read, some parents are less interested in the class photos now because they've got scads of pictures of their kids, now that just about everybody has a digital camera.

Then there's the technological advancement of superimposing two images in the same print, which allows for wondrous photographic achievements such as this.

(Photo from wastetimepost.com)

This is Jia Wen's school picture. I think this one turned out pretty well.

(Photo from A Mum's Hideout)

The mystery yearbook photo is of Joe Biden.

Sources

Shannon Thomas Perich, Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, "Photography Changes How We Choose to Recast Experience" (it's actually about the history of George K. Warren's photo albums)

Library of Congress Memory Project, The Daguerrotype

Skinner, How to Identify a Daguerreotype

Katherine Rosman, It's Picture Day, Say 'Cheesy', The Wall Street Journal, November 10, 2011

Historical Value of the US Dollar

- But, some parents say, they don't actually have any on-paper photos of their children. So they like the class pictures because they get an real, tangible print of their child that they can put in their wallets or prop up on the mantelpiece.

- Wanting a photo of someone you care about -- that hasn't changed at all.

This is Jia Wen's school picture. I think this one turned out pretty well.

(Photo from A Mum's Hideout)

The mystery yearbook photo is of Joe Biden.

Sources

Shannon Thomas Perich, Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, "Photography Changes How We Choose to Recast Experience" (it's actually about the history of George K. Warren's photo albums)

Library of Congress Memory Project, The Daguerrotype

Skinner, How to Identify a Daguerreotype

Katherine Rosman, It's Picture Day, Say 'Cheesy', The Wall Street Journal, November 10, 2011

Historical Value of the US Dollar

No comments:

Post a Comment

If you're a spammer, there's no point posting a comment. It will automatically get filtered out or deleted. Comments from real people, however, are always very welcome!